The 2027 election campaigns have been effectively launched already – a full two years in advance.

So let us talk about the role of money in such election campaigns.

My perspective on this is influenced by something I have heard from many politicians over the years: that it is a mistake to “start spending too early” because you are sure to run out of money before election day.

This is said to be true as much for those who win, as for those who lose, in any one election.

And I have never been able to figure out whether the greater pain is felt by those who were effectively rendered bankrupt in the process of losing, or those who ended up bankrupt a few years after winning.

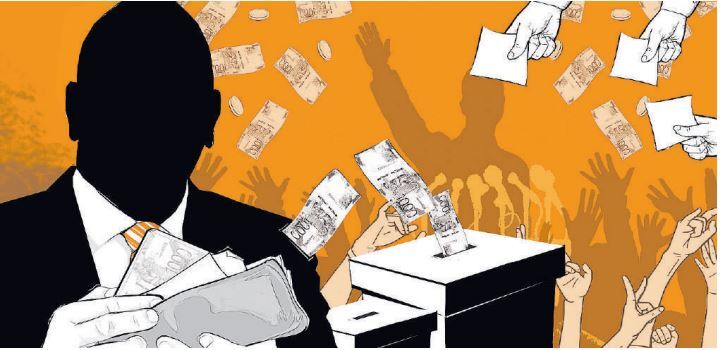

What is indisputable is that election campaigns in this country, and at every level, bring out the worst in both candidates and voters.

Starting with candidates, I would say that given how expensive Kenyan elections are, it does not take long for the candidate to be “over-invested” in the process.

Having spent so much in just the early phases, they are then doomed to spend even more in the quest for victory, on the logic that “if I lose, my money will have been eaten for nothing”.

As for the voters, they present an odd contradiction: while declaring all the time that they are “only interested in development”, they will demand payment of some kind or other, even just to attend an outdoor meeting at which the candidate is to tell them just exactly how he or she intends to deliver this “development”.

The inevitable declaration of every losing candidate in any election, is “Don’t these fools know that the person they have voted for, and who basically just bought their votes, will now have only one objective, and that is to get back the money he or she spent on the campaign, by stealing from public funds?”

But whereas there is no doubt that Kenyan elections – with very few exceptions – involve a lavish outpouring of funds at every level, just how effective this money is in securing the desperately sought victory, is not easy to estimate.

For example, I would speculate that no presidential candidate has ever spent as much money (in proportion to the size of the economy at that time) as Daniel Moi in the 1992 election.

But he was not able to get more than about 40 per cent of total votes cast, despite outspending the opposition candidates many times over.

And just about every corner of the country has seen a candidate who seemed to have limitless funds available for his or her campaign, end up losing badly to a rival who did not really spend all that much.

Other factors clearly count for a great deal more than just the gross expenditure on caps, t-shirts, posters, banners and other such campaign paraphernalia, in addition to transport costs, security and the ever present “mobilisation fees” (now more often referred to as “facilitation”).

My idea here is that Kenyans are in general, complicit prisoners of “identity politics”.

Once pledged to the perceived interests of their regional community, tribe or clan, under an acknowledged “regional kingpin”, they cannot easily shake off their loyalty to this pledge.

And the best way to understand this is by a comparison to the English Premier League football matches.

Not being much of a soccer fan myself, I do not really follow the Premier League very closely. But who among us does not know someone who does?

This would be a man (the dedicated fans are mostly men) who will lose his appetite if “his team” loses; who proudly wears the shirt that identifies him as a supporter of Chelsea or Arsenal or Manchester City; who each time he changes cars, immediately applies to the new car a sticker that has the logo of “his team”.

And all this fuss is over a team playing football thousands of miles away, and millionaire footballers who – when it suits their purposes – will go over to a different team which is able to pay them more money.

In other words, the players who score the goals and whom the fans worship are nowhere near as loyal to that club, as the fans are.

The fans’ identity is tied up with the football club. While the star players’ interests are in how much money they can make, while still at the peak of their skills.

by WYCLIFFE MUGA