Ngugi: Please don't cry for me, cry for beloved country Kenya

Were it not for the grave claims about my alleged destitution in America, there is a comic feel to the fictive constructs that have emerged since my recent profile in The Guardian “went viral.”

This calls to mind another spectre in 1986, when policemen were deployed to the streets to apprehend an insurgent whose name was Matigari, a character in my allegorical fiction by the same title. When they failed to find the suspect, they raided bookstores and carted copies away.

That wasn’t the only instance when life was imitating fiction; my novel Caitaani Mũtharabainĩ, translated into Kiswahili as Shetani Msalabani and Devil on the Cross in English, anticipates a State run by thieves and robbers.

The new Kenya Kwanza administration is dominated by individuals of questionable integrity, and who have faced just about every imaginable crime in our statutes, including theft and robbery.

I digress. The expansive Guardian piece by the Kenyan writer, Carey Baraka, looked back on my lengthy life of writing, through our three days of interaction at my home in California, last November. I understand Baraka has been subjected to online vitriol for what was seen as intrusive, unethical journalism by exposing my medical condition.

- .

Keep Reading

- I did not let my challenges stop me from achieving my dreams

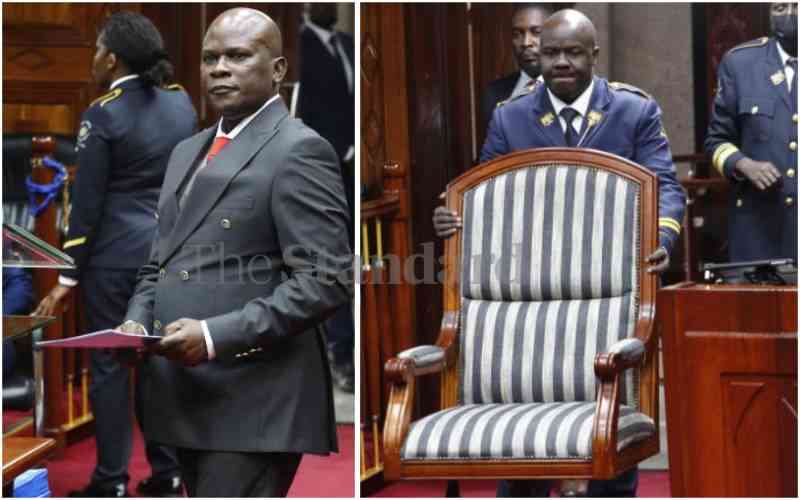

- William Oduol disowns Sh1m chair, exposes more rot

- If novelist Ngugi wa Thiong'o is not a national hero, then who is?

- Get checked if you can't start pee or pee too often, at night

For the record, I shared my story with him as a way of creating public awareness about prostate cancer, as it disproportionately affects black men due to their genetic disposition. Every black male over 40 years should go for medical check-up on his prostate once every year.

If detected early it can be treated and thus prevent many untimely deaths. There is nothing to hide about prostate cancer. Baraka’s story, indeed, was a very truthful capture of the mood at that time, as I prepared for a medical procedure for my kidney failure.

Having read The Guardian story several times, I have no idea how some folks have imagined that I live a desolate life, on the fringe of destitution in America. I am busy at work as a writer, while still serving as a Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature at University of California, Irvine.

Even as retirement looms, at 85, I am blessed to have worked continuously since 1968, and so I hope I will never suffer want. And I’ll be able to spend more days with my family and friends.

As Baraka wrote, our conversations were interrupted by conversations with my children, who constantly check on me. I feel blessed for the support I have had from my entire family in Kenya, America, England, and Sweden. My three granddaughters Nyambura 1 and 2 and 3, my grandson Mĩrĩngũ and his beautiful wife, Wanja enjoy the grand performance that is me, the grandfather telling stories to my grands. w

I would encourage Kenyans to read The Guardian piece for themselves. But I would like them to go further and read the body of work produced from the struggles, not just by me, but the critical mass of students, intellectuals, church, and union leaders through the 1970s to 1990s. These are largely unknown to younger generation of Kenyans.

I’d recommend our young patriots to read the archives at Ukombozi Library in Nairobi as it documents the activities of the London-based Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners, of which I was an active member, after I was pushed into exile in 1982. The archive also hosts materials from the December Twelve Movement.

My detention without trial in 1977 was precipitated by a Gikuyu play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), which I co-wrote with Ngugi wa Mirii. For writing in my mother tongue, Jomo Kenyatta sent me to a state prison; Daniel arap Moi sent me out of State. Uhuru Kenyatta received me in State House in 2015.

As our nation marks 60 years of independence, it’s opportune for us to reflect on our evolution as a society and the sacrifices that intellectuals, artists and activists have had to endure to democratise our country.

Exile, after all, is a last resort for anybody, particularly for writers who are committed to social change in their land of birth, for they need to be in constant commune with the every day.

Even more importantly, have we built institutions that can safeguard rights of the citizens so that no one shall ever go into exile for expressing their thoughts? And is our country safe for those who espouse a different pathway for a more just and equitable society?

Kenyans should not forget that upon my return to Kenya in 2004, after 22 years in exile, my wife and I were brutally attacked by gun-wielding goons while staying in one of the most secure neighbourhoods of Nairobi. Please don’t cry for me. Let us cry for our beloved country. We should reflect on the threats to the freedoms for which soldiers of Kenya Land and Freedom Army led by Dedan Kĩmathi fought so hard to liberate.

Reading from afar, it is concerning that threats to a free Press, runaway corruption and parliamentary acquiescence of the Executive are a recipe for the sort of nightmares that roiled our nation in the past. But that should not lead us to despair but renew Kenyans’ collective resolve to secure their hard-won freedom.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, a pioneering Kenyan writer and cultural theorist of international renown, has published several dozen books in a career spanning nearly six decades. He’s Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature at University of California, Irvine.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Post a Comment