On a dusty construction site at Lumumba Drive in Kisumu, 27-year-old mason Joseph Otieno wipes sweat from his brow.

He earns just enough to send some back home to his native village in Siaya, but his biggest worry is whether tomorrow will bring work.

“Sometimes we wait for weeks to be called. If there are more projects, at least we know we can eat,” says Otieno.

New research by the Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research offers a glimmer of hope for millions of people like Otieno.

It suggests that if the government’s Bottom-up Economic Transformation Agenda achieves its growth targets, Kenya could create 1.8 million new jobs every year.

The projections not only surpass the official goal of 1.2 million jobs under the Fourth Medium-Term Economic and Social Development Plan but also highlight a sharp contrast across sectors, raising questions about where the country’s real employment opportunities lie.

The findings paint a complex picture of Kenya’s labour future—one where infrastructure and agro-based industries promise the most opportunities, services like education and tourism emerge as powerful indirect employers and the public administration sector faces a steep decline.

According to the study, if all BETA pillars could have achieved their 2024 growth targets, 1,788,881 jobs could have been created in a single year.

Of these, about 407,000 would be direct jobs within expanding industries, while 1.38 million would be indirect, generated through supply chains and related activities.

By contrast, if the economy continues on its current trajectory, growth could generate an even higher 1.88 million jobs—though researchers warn that this scenario depends heavily on maintaining exceptionally high growth in infrastructure seen in 2023, which is unlikely given fiscal constraints and budget cuts.

“This evidence suggests that Kenya’s employment potential is far greater than we are planning for, but it requires bold policy execution, investment and targeted interventions,” says Boaz Munga, policy analyst at KIPPRA.

According to the report, the strongest drivers of employment lie in construction, transport and storage, and tea production.

Construction is projected to add 373,816 jobs, although most of these would be indirect. Its labour-intensive supply chains—from cement to steel to skilled artisans—make it the single largest job generator.

Transport and storage, buoyed by expanding logistics, is expected to add 309,538 jobs. This reflects the growing importance of Kenya’s position as a regional trade hub.

Tea, one of Kenya’s most established export earners, could create 152,552 jobs, mostly in rural farming communities.

Other notable contributors include accommodation and food services (59,497 jobs), textiles and apparel (40,330), dairy (22,491), and ICT (24,407).

“These findings highlight the dual promise of Kenya’s traditional strengths, like agriculture, and new growth sectors like ICT and logistics,” said the report’s co-author, Violet Nyabaro, who is also a policy analyst.

However, while most sectors are expanding, public administration is expected to shed more than 77,000 jobs, making it the only pillar to experience a net loss.

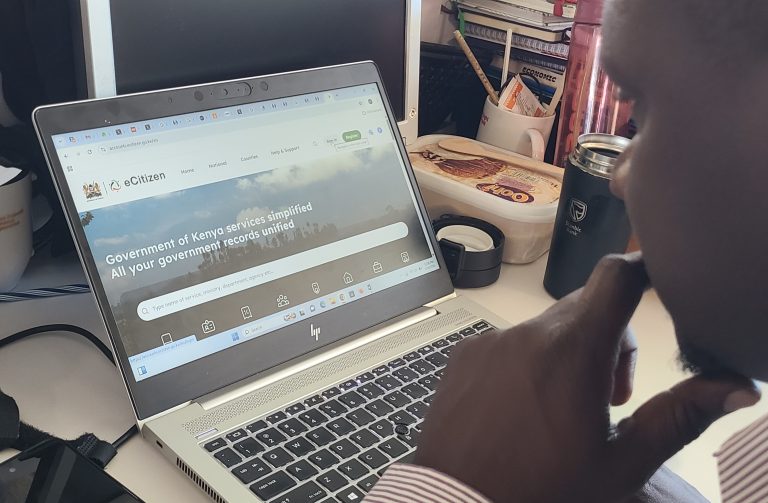

The decline, the report suggests, is linked to digitisation, austerity measures, and technological adoption in government operations.

While some indirect roles may emerge in related industries, the reduction in direct employment—particularly in administrative and clerical roles—underscores the pressures facing the public service.

The findings also show a major structural shift. Services, particularly education, ICT, and tourism, are emerging as stronger job creators than industry, despite the longstanding government focus on manufacturing.

For example, education is expected to generate over 34,000 jobs indirectly, even as direct teaching and administrative roles decline.

Similarly, tourism and hospitality could add more than 59,000 direct jobs, cementing their role as a grassroots employer, especially in rural and coastal areas.

By contrast, manufacturing sub-sectors such as textiles and apparel, though important, lag in absolute job creation.

KIPPRA says that Agriculture remains central, but its employment potential is fragile. Tea, dairy, and agro-processing all show strong growth, but dependence on rain-fed farming makes them highly vulnerable to climate shocks.

The report warns that unless Kenya invests in irrigation, mechanisation, and climate-smart technologies, jobs in these sectors could fluctuate dramatically, undermining rural livelihoods.

“Reducing reliance on rain-fed agriculture will strengthen tea, dairy, and agro-industries, ensuring job resilience,” the study reads in part.

In the service sectors, tourism and hospitality stand out. The accommodation and food services industry alone is projected to create over 153,000 jobs under current growth rates.

“From homestays in Kisumu to beach resorts in Mombasa, tourism provides rural communities with direct incomes and spin-off opportunities in transport, crafts and farming.” The report says.

Senior policy analyst Shadrack Mwatu says that another challenge is the mismatch between skills and job demand.

Agriculture creates low-skill, often informal jobs, while construction, mining, and manufacturing increasingly demand technical and higher-level skills.

Yet Kenya’s education system continues to produce large numbers of graduates without the vocational training or practical competencies demanded by industry. This mismatch risks locking young people out of the very sectors that could power their future.

“This disconnect can be attributed to various factors, including limited diversification of economies, inadequate investment in sub-sectors with high employment potential and inadequate skills development programs that align with market needs,” he said in the report.

Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) feature prominently in the report as the true job engines.

From artisans in construction to small-scale tea farmers and textile producers, MSMEs account for the bulk of job creation potential.

However, their success hinges on access to credit, technology and markets. Without targeted support—such as affordable financing, tax relief and digital adoption—MSMEs risk being stifled even as policy papers tout their importance.

by JACKTONE LAWI